Interview with Carl Gopalkrishnan

When we first sat down with Carl Gopalkrishnan to discuss his visual arts submission to Collateral, we had more questions than time allowed us to ask. Carl’s work as an artist strives to confront multiple identities—his own, and the interdependent, always-shifting identities of human culture—in ways that are open, vulnerable, and unafraid of the ugliness or uncertainty of what it means to survive on this war-stricken planet in the twenty-first century. His perspective as a queer Chinese-Indian-Australian born in England (with an acknowledged reputation as a ‘war artist’) informs his interest in the spiritual, mythological, and psychological ways the human family has less to divide it than it has in common. He speaks to the artistic struggle against censorship, particularly as it affects marginalized artists, and the control nations have and would like to have over publicly acceptable art.

We began at the beginning, and we got as far as we could, for now. Here are the highlights.

Collateral: How and when were you initially drawn to the visual arts?

Carl Gopalkrishnan: I’ve been drawing and painting since before I learned to write, like most kids, but for me it continued as my primary expression, I suppose. I thought visually before I thought in words. I was a very interior child. [My family] travelled a lot, and I think constantly changing cultures, languages, and places confuse some kids. It’s exciting of course, but also confusing, so my inner life was where I went to process the world from a very young age.

[My high school] was a catholic boys’ school, not a great place for me, and not supportive of creatives. Again, retreat into my interior visual life and making art. I dropped out of high school and fell in with some musicians and other artists during the early 1980s. The 1980s were fun but dangerous; it was the AIDS crisis, and being gay was illegal. The city I lived in (Perth in Western Australia) was also experiencing a right-wing anti-Asian terrorism spree of Chinese restaurant bombings that made international headlines. This was less than a decade after the dismantling of the White Australia Policy, so we were early migrants during that time, and I had to go to school in that atmosphere, with swastika stickers at the bus stop. After dropping out of school at 15, I did a work experience at a publishing wing of the Education Department as an illustrator at age 16. Traditional pen and ink, painting, drawing, and that inspired me to enroll the next year in the local graphic design course at the technical college.

In 1984, fine art and commercial art sat in the same course; this is before computers, so it was design-oriented with bits of live drawing thrown in, and art history, and making tv ads, and writing copy, and designing packaging. I was drawn to typography, but I was known as “that fine arty” kid, because my designs were so painterly. At home, I started painting in earnest from about age 18 and never stopped. But I never thought of myself as an “Artist” because of that course. I was terrible in advertising, hated the environment, so I worked in fashion textiles in Melbourne in 1989, painting at home still. Returning to Perth, I went to get one of [my works] framed, and the gallery loved it; they offered to throw me a solo exhibition for free and that’s how I started out.

My inspirations at the time were numerous. As a designer we were all obsessed with the UK magazine The Face. Typography and fonts were very hip back then. My teachers were older, traditional, Bauhaus-influenced designers. My typographer lecturer was a control freak trained in Basil, Switzerland. I didn’t meet many painters till I left design school, but I was a fan of Friedensreich Regentag Dunkelbunt Hundertwasser, the Austrian artist and architect. I loved the surrealists, and Miro, and developed a real passion for Outsider Art, which was also called Art Brut. So, I was limited in my early exposure. Then I started working as a gallery assistant at a small avant garde gallery in Perth called Bridge Gallery, where I first exhibited, and that is where I learned more about painting from generous older painters who were happy to talk to me and share their techniques.

Life was slower in the 1980s; people took more time to research and reflect, and they took ages before making marks on the canvas, or scratching marks into their etching plates. It all felt slow and deliberate. That is the best education really. I never use the design stuff, but I use a lot of those older processes and materials today in my own art. I prime my canvases with gesso at least eight times and sand it down. I always allow layers to cure/dry, because I use acrylic and it’s not about making acrylic paint look like oils. Acrylic paint is a lot more multifaceted and layered. I’ve worked with it for over 35 years now, and I keep stretching it. I keep teaching myself. I also created my own process in terms of the research. I was more drawn to history, philosophy, psychology, and literature, and I now integrate performance into the painting process.

Over time, art has merged into who I am; I use artistic processes in all areas of my life, so the division between my art and my various day jobs isn’t always clear. I have this intuitive capability that art gives me what I need in all areas of my life. All areas of my life and the world then bleed back onto my canvas, so I don’t keep my art in a little box. It’s the entire way I see the world and live my life.

Collateral: You’ve said that you began to confront war and conflict in your art post-9/11. What were you hoping your art could do then? Has that hope changed or crystallized over the past 23 years?

Carl Gopalkrishnan: I think we were all in shock at the changes to the world after 9/11; a lot went downhill, and a lot remained “normal”. Around 2003, I started some small drawings after taking a break from art, and it was just there, for me, this post-9/11 reality. It made me ask questions, and then I started reading books, poems about war (at first, those of Wilfred Owen, T.S. Eliot, Herbert Read, as well as ancient Chinese and Greek poems, and Nikolay Mayorov’s “We Are Not Blessed”) and then reading a lot of research papers from the Pentagon because technology was changing so fast. Drones were just becoming a thing, and we had all failed to stop the war in Iraq with demonstrations across the world. So we were at war again (after the Gulf War) in Iraq, and we now know that our involvement was based on false information. So that was the era. And artists soak up the era.

In Australia, there was a huge wave of censorship in the arts, and artists being questioned, exhibitions closing down, art being vandalised. Artists express what they see and feel, and when that isn’t politically convenient, we are easy scapegoats. Since 9/11, Australia has legislated the most counter terrorism legislation in the world, to the point that it has changed the national cultural identity. Australia and America, as allies, have a long cultural history, and as a person of colour, a lot of us were impacted by Islamophobia even if we weren’t Muslim, because so much of the post-9/11 wars have this racial element that continues today. So, in a climate of censorship, and as an artist just wanting to make art, I was challenged to find new ways to speak about this. I learned a lot from this censorship, and I studied war doctrines, policies, and technology in order to be as relevant to the times as I could.

I also studied my family history more and I could not get away from the experiences of my mum and dad, as children of the Pacific War and Japanese occupation. Lots of horror there, and intergenerational trauma in my family and among their friends. So I began to see patterns of stories, and I began to hear the cultural, religious, even cinematic Hollywood stories about those wars. That led me to read more, and to interview more veterans. That process itself was difficult; not all of them were healthy people. I learned about the failure of our militaries to properly re-integrate soldiers to civilian life and how that spirals into a range of other social problems. I think art, at the end of the day, allows for creative and unconventional ways of asking questions that policy, psychiatry, and psychology just don’t have the tools to deal with.

It has occurred to me that the original aims of war artists from the two world wars have frequently been distorted in favour of military involvement in many ways. In Australia it became a ‘thing’ for artists to become embedded (like journalists) into the military in very controlled ways, given basic training, and not encouraged to paint the full picture, but paint formal portraits that celebrate doctrine instead of excavating the full, uncomfortable truth of war: those truths I was getting from my parents, from my ethnic community families in my job, from former soldiers who had no qualms about telling a curious artist about the realities of war.

Civilian stories were being cut out, or became background collateral, necessary to telling a particular military story. Creativity was coopted to wash over mistakes, fears, fuckups, bad doctrines, bad calls, bad people. They were rewarded as celebrity artists in their camo cargo pants in magazine spreads, holding their guns and brushes in the same hand. That’s when I started seeing my paintings as a form of ‘war art’ from a civilian perspective, from a cultural viewpoint, and my work has been exploring the depths of that idea for about the last 24 years.

My hope was to redefine ‘war art’ away from this misuse of ‘war artists’ being recruited for the military PR payroll. Has it been affective? Who can say.

In 2012, I was invited to contribute to a high-level workshop in the UK centered on drones and international intervention and I think it did open the minds of some people to the cultural politics of international conflict. They were unusually open-minded, but some of them were pretty high-level players. But I don’t think even they were listened to with their concern about the normalisation of targeted killing and assassinations, and the way international law and the rules of war have become so abused to the point of breaking down the entire post World War 2 international framework.

I think where Gaza is today and the damage being done to our expectations of both what is a just war and a just prosecution of war, it didn’t just happen over the past year. It began two decades before and can be traced to the world’s reaction to the CIA “enhanced interrogation” programs at Guantánamo Bay; and when President Obama’s Attorney General Eric Holder advocated for targeted assassinations without judicial review to kill terrorist operatives overseas even if they were American. That made everyone’s jaw drop. That is when I saw the love affair between America and the rest of The World pause. And it was a love affair but it’s over.

I did a painting where I saw the statecraft between the nation-state of America and the nation-state of Israel as the marriage from the 1952 Hollywood musical A Star is Born with Judy Garland and James Mason. Mason’s character, Norman Maine, is a top Hollywood star and alcoholic on his way down, while Judy Garland’s Esther Blodgett is rising. The American Jewish interfaith magazine Tikkun featured me as their Artist in 2011 and interviewed me about that and other paintings through their values of Tikkun Olam, which is Hebrew for ‘repairing the world’. I have always thought of the politics in my art not as politics, but as a landscape for the subconscious myths and stories that drive them. If I could help people to see those stories, and to own them, then it might give them the courage to try to change those stories. It might also inform de-escalation strategies between “enemies” and expand creative thinking of military minds so they could invent better options to fight asymmetrical urban wars than by obliterating all civilian infrastructure.

In that sense, and not being Jewish myself, I felt then and still do that my art is as much a part of the Jewish Tikkun Olam as it is of the social justice values innate within Christianity or Islam and indeed most of the Eastern religions from my own cultural heritage here in the Asia-Pacific.

Collateral: How did the Gaza Trilogy begin? What sustained it?

Carl Gopalkrishnan: Like the whole world, I have been a witness to the wars in Gaza for some time. It was the war in 2008 when I felt it cut into my consciousness as an artist, while I was dealing with the post-9/11 years. I was exploring American exceptionalism, and how the wars of 9/11 were affecting that creative legacy of literature, film, art, and self-identity. When I say affecting, I mean damaging the soul of the American psyche, which has nurtured all this amazing soft power creativity and reshaped the world in its own image. So, it was about how I saw America losing its creative spirit, and I think my motive was to warn against this.

The three paintings I did for the Gaza Trilogy were, for me, a continuation of that storytelling and warning. I suppose I think less about my “imaginal” process and more about the ideas people ask of me. I have always, from a very young age, experienced strong images and sensations in my imaginings that have stayed with me into adulthood. The less safe word for it would be “visions.” I think in a secular, science-oriented society, we like to downplay, or suggest that what is non-explicable to science is not ‘reasonable’ and therefore not legitimate, even in art. That is quite different, I think, as you move between different parts of the world and outside the western framework where I live in the Asia-Pacific. So faith-based can be ideas of the intellect, or actual experience, and Art made from that also is shaped by those different ways of seeing the world.

For me, having strong feelings that become clear vivid images and statements from my mind, or completed essays that literally “download” without much intervention from me, is normal. In psychology, the closest I have found to explain my process is the work of American imaginal-psychologist Mary Watkins, and two of her books which not entirely, but somewhat, explain my process in our rational language: Waking Dreams (1976) and Invisible Guests (2015).

I’ve written previously about each of the Gaza Trilogy paintings. Here are some excerpts from those essays [edited for Collateral]:

“In each painting Gaza’s children are dead, but dead in different ways. In my first canvas, ‘Gaza, Monsters of the Id: A Painting in Red, White + Blue = Lavender,’ the children are in blue plastic body bags, which surely isn’t where most have ended up, since many will never be recovered from under the rubble. Many will die from disease and damaged organs, from poor amputations without anesthetic, perhaps years after a ceasefire, without their deaths ever being counted. In this painting the bombing is happening, but we don’t see this reality. Instead we see metaphors. Those witnessing this genocide are becoming either desensitised from too many videos from Gaza, or they are refusing to see, speak or think that a genocide is occurring. We are splitting into tribes, for and against. Our societies are fragmenting. Friend against friend. Colleagues against colleagues. Family against family.

There is a reference to ancient religious prophecy in my use of symbols from ancient amulets and cultural artifacts of colonisation such as the golliwog doll. A difficult focus of my painting is the line of blue plastic improvised ‘body bags’ tied up at the head & feet of unidentified/unclaimed Palestinian corpses. They form a horizon separating & connecting both the physical war from the spiritual & mythological war (or the Underworld).

The dogs of war here become one big dog of war backgrounded by a mythical beast—our subconscious Ids—covered with ancient symbols and letters. The beast has become an amulet in itself, mirroring the fears of ancient Christianity, Judaism and Islam. These religions with angels and demons, Satans and Gods, prophecies and doctrines have difficult relationships with their magical, mystical and supernatural elements. Superstition is the bleeding of this relationship from the Underworld into our social media.

We have inherited these split personalities, but we do not own them, and as a result they still control our narratives of war and peace. Similarly, when we program Artificial Intelligence (AI) with our own limited beliefs and doctrines of faith, they will act as we do. Like Israel’s US funded and developed AI targeting system named Lavender, it will repeat our human histories of war. The painting is themed in the colours of red, white and blue which, when combined, also create the colour lavender.”

“In ‘The Curse of the Eighth Decade: The Children’s Hour,’ the children trapped under the rubble and buried in plastic are decomposed, their eyes the only representation of their past identities. The drama is always occurring twofold, as represented by figures above and below the horizon. It is the political drama above The Underworld of subconscious thoughts and ideas embedded in religious doctrine such as The Mishnah and its reference to a Red Heifer, the essential character in the Curse of the title.

The curse refers to the destruction of the third Temple of Israel and groups of Jews, evangelical Christians and Muslims who carry deep fears around this narrative. The central thesis of the curse is a contested hilltop in Jerusalem and desire to rebuild an ancient temple on which the Islamic shrine The Dome of the Rock now stands.

When I looked further into this curse, I found varieties of interpretations but a powerful belief across all faiths which I didn’t expect to see in 2024. Muslims, Jews and Evangelical Christians remain tied to each other through this mythic story, so it seemed an important story to paint specifically in the town of Rafah. As neither Jew nor Muslim but from a multifaith life experience, the Third Temple seems not only a physical building and place of worship, but a renewal of identities exhausted by false promises of atonement for past trauma. Our concepts of God need to be equally renewed because they are killing us.

I am deeply disturbed by how the language of purification repetitively precedes genocides throughout human history. In my painting, the dogs of war return, carrying the weight of our imagined Jesus. Like him we watch and recognise the precursors to previous cycles of trauma, pain and revenge. We watch medical aid get blocked, allied countries watch powerlessly and we ask, as Jesus foresaw himself in the Garden of Gethsemane, “Lord, why hast thou forsaken us?” In the smoke-filled skies plague doctors from the Middle Ages reach out to pierce medical workers in Rafah. The scenes of destruction evoke equal horror from Jewish people of conscience and devout scholars who ask, where is the Judaism we know?”

“‘American Mnemosyne: A Valkyrie of Atonement’ evokes other religions in other times in the form of the ancient Greek goddess of memory, Mnemosyne, and her nine muses. It is set in the future, after a Gaza ceasefire has passed many years. The horizon again reminds us that the past is ever with us, with clear fields of soft green leaves washing away the memories of the Gaza genocide.

But a Valkyrie descends from the sky, and we are mesmerised and caught initially in her role as a guide of dead soldiers to Valhalla to fight another day. She is also the goddess of memory Mnemosyne in disguise with her nine muses. Though decomposed and lost, Gaza children recognise the Muses and see them as teddy bears: pastel, warm, friendly and kind. Unbeknownst to the children, she is also the American holder of Military Memory.

The Valkyrie/Mnemosyne is inspired by a likeness to the author Elizabeth D. Samet to intentionally evoke her thesis, Looking for The Good War, which unpacks the power of creativity and storytelling in the arts to affect how we feel about the past to change the present.

In this imaginary future, America now has memory, and knows it is complicit in these children’s deaths. The Goddess of Memory brings not politics, ideology or doctrine to the killing fields of Gaza, but the liberal arts and the poets to heal their souls. She brings the muses of music, theatre, writing, epic poetry, dance and tragedy and comedy. She brings the knowledge of science and the stars. She knows that memory and pain can only be forgotten through repetitions of joy, creativity and love.”

Collateral: What do you hope this work can do?

Carl Gopalkrishnan: I hope the viewer of these paintings can reflect on a few different realities when they think about the genocide in Gaza. I hope they might consider the possibility that all children’s lives matter, and try to imagine what conflict and wars might look like if avoiding the killing of children became the central rule within every nation’s defence doctrine. I hope they will learn to think more creatively about the causes of war, and to better identify when religious mythology and past national trauma is embedded in their nations’ military doctrines. Finally, and in my last canvas, I hope that the US and its allies realise that to heal and disarm the long-term seeds of hate planted by the suffering and death of so many Palestinian children, they will need to do more than throw money at them through foreign aid.

By allowing an honest memory of its role, American guilt can lead to atonement not just by giving money and aid, but by a deep and inspired use of its artistic, literary, philosophical and spiritual legacy which it has neglected. In so doing, the trilogy prophesies not a lesson of charity, but of a much deeper transformation of the American soul than the tools of politics could ever achieve.

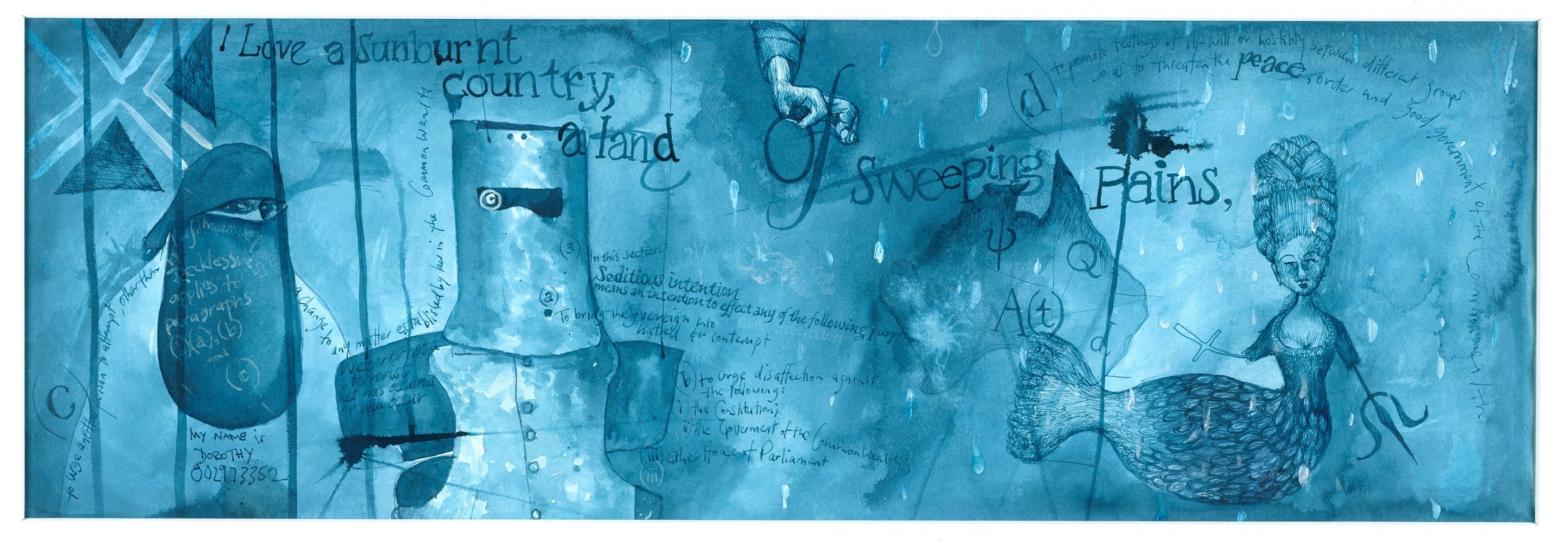

“Dorothea Mackellar Has Been Detained” from Sedition + Other Bedtime Stories (pen, brush, ink on paper). Gopalkrishnan writes, “Dorothea McKellar was a poet who wrote an iconic poem called ‘My Country’, which we had to learn as kids at school (though not anymore, I hear). The poem defined Australia by our relationship to the land, from the voice of a white woman. So, in this piece, I contrast the land we love with how it is experienced by refugees and migrants in detention camps offshore while classed as ‘illegal immigrants’ and their visas are processed, often for years. They were collateral damage from the War on Terror years, which speaks to how we are now trying to ban Palestinian refugees, at least in Australia.

Collateral: Do you have a message we can help deliver to other artists around the world creating work that intentionally starts difficult conversations in the face of censorship and suppression?

Carl Gopalkrishnan: I realise now, nearly four decades later, how different my art would have been if I had relied or become dependent on the arts grants system of governments early on. For so many artists, that’s what they begin with, and then institutionally again, the parameters for creativity are already set. [Moving away from that] gave me freedom from the beginning as an artist, not even calling myself an artist, just making art as a natural expression of who I am.

We can’t start difficult conversations if we haven’t learned to think for ourselves. If we have, then we can see the agenda in those briefs, those grants, and decide if they will allow us to see, think and express the world unimpeded in our work.

So, when the commercial gallery doors closed here in Australia, especially after my shows about Australia’s anti-terrorism legislation in 2006 and then my Gaza paintings published in 2011 in Tikkun Magazine in the US, I had to re-think what an art career looks like, indeed what ‘success’ looks like. Here are some of the lessons I’ve learned:

Build a support network

It’s always been important (if your art questions power) to nurture relationships with smaller, independent galleries that have specific, written policies of welcoming minority opinions. Don’t assume a progressive tone will lead to actual support for the content of your work. If they don’t spell it out, build their business around those values, then they don’t mean it. So trust the right people and build a support network before you try to change the conversation.

Decide if art is your vocation or a career

I think it helps to know yourself. Is your art practice also a vocation, or just a career? That’s an important distinction to know when you’re paying the price of exclusion for intentionally trying to start a conversation during times of censorship and suppression. It also helps if you don’t ask difficult questions and are criticised by progressive voices for your ‘silence’ or ‘complicity’. I’m less harsh on people who are trying to make a living by intentionally making art which is decorative. Artists, however, who use their creativity to sell government, military, and corporate agendas which kill kids, well, I avoid them, which is hard because they are often in the top tier of our creative industries. If you have a vocation, it will be harder to turn off emotionally, but that need not diminish your professionalism when people accuse you of being naïve, misguided or amateurish for having a different opinion.

Go beyond Google in your self-learning

It is more important today to do your research beyond Googling things, because so much more is not archived or made available on the internet than you’d think. I only know this because I am from another century (literally). Knowledge and insights are being lost, and algorithms present a skewed number of options that bring you back, like Alice in Wonderland, to these potholes where you think you’re free and making a difference, only to discover that you’re exactly where they wanted you to be—nutted. Suppression and censorship happen on multiple levels, including self-censorship and covert invitations to shut up and take the money. By all means, take the money when necessary, but try not to sign any contracts.

Accept not being liked

Become really comfortable with not being liked or respected or invited to the next big thing. I’ve had periods where I tried to sell out, and you know, you definitely eat, sleep, dress and spend better for a little while, but if you are in it as a vocation, you can’t maintain it, and you won’t be able to keep your mouth shut for long. So, during those times of weakness, take all the booze from the fridge, towels from the hotel bathroom, selfies with important people, and save a LOT OF MONEY for the lean years when you’re blacklisted.

Know the difference between Artist and Activist

I have learned over time to make a commitment to my values, not my feelings. Feelings matter of course, but they come and go, and they more often deceive you. They are great to kick-start you, but they don’t travel with your actions all the way to the end, which can confuse artists that over-rely on inspiration and not perspiration.

Of course if our feelings turn out to be right, great; keep your opinions and start those conversations, but if we start to doubt ourselves and others we believe in, it’s not a failure. We develop our own opinions, and then paint, sing, act, and write from that space.

So, as artists, ask yourself: are you an Activist or an Artist? Are you both? Do you have a method of your own making to test yourself against those terms? You do? Great. Make art from that space. That is Art, not necessarily Activism. The manner in which our art enters and interacts with the world can’t be controlled.

I don’t confuse my roles. I have a day job in policy and advocacy. When I am learning, reacting or expressing the world through my art, holding the mirror up to the world, as Nina Simone famously explained, then you are an artist, and a citizen I might add, being active in the world. Being active in the world, as an Artist, is as valuable as being an Activist, but they are not the same things. Was Picasso’s painting Guernica Art or Activism? You tell me. Every generation and every individual should answer that question differently. An artist that is comfortable with being uncomfortable is better prepared and trained to lead others through difficult conversations.

“Angels and Pears 2009” from The Assassination of Judy Garland. (acrylic, screenprint, and gold leaf on canvas)

Collateral: What upcoming publications or exhibits do you have planned or in progress?

Carl Gopalkrishnan: In November 2024, I’ll appear in Vala Issue 5, the journal of the Blake Society in London, with a collaborative photographic performance art essay I did with a portrait photographer in Perth named Juliette Scott. We started out initially with two separate projects-my Vala submission and her desire to explore drag, and that issue of drag really got me thinking about William Blake and his challenging women’s role in society in 18th century London. A lot has been written about his attitudes toward free love, and his poetry really challenges the dualistic thinking in government, religion and imperialism, including slavery.

To me, a lot of Blake’s art and poetry is actually gender ambiguous (some of his visual/literary characters change form, reproduce in a god-like manner, or merge with his mythical characters), so we created five characters and our stylist, Marica Furlan, helped me to create these characters, which I performed. They challenged how we see Blake’s God, not only as female but as gender diverse and LGBTQ. So that comes out in late November both online and in print.

I have an un-exhibited body of work that was shelved during the pandemic, and the few independent galleries I loved closed down, so it’s still sitting there. It’s called “Boy on Electric Scooter in Collapsing Universe” and includes paintings and prints from 2015 to 2024. It is definitely mirroring the many changes within that decade. Personally, for me, my dad died in 2018, and we went into the pandemic, plus social media extremism and now global conflict and climate disasters. The title reflects how I feel within all this fast-paced change. During the pandemic I started an online shop, as many artists have learned to depend less on physical space.

Carl Gopalkrishnan

I hope I can get that exhibition together in 2025 somewhere, but I’m moving into a new narrative arc called Revelation now, which is, I guess, my own version of religious art, whatever that means. I started creating amulets in 2023 after researching the role of superstition in military life, and that is going to be part of the new phase—learning to work with ceramics. I’m enjoying working with the clay.

***

For more information about Carl and his work, please visit www.carlgopal.com