Visual Arts

“It was the first time I realized a child could die—and I was a child.”

We recently sat down with Teruko Nimura, visual artist based in Washington state, for more of a conversation than interview. Her diverse multi-media practice includes installation, sculpture, drawing, video/performance, social and public art. She is interested in themes of interconnectedness, collective memory and trauma, cultural, racial, and female identity, motherhood, and the climate crisis. Her varied explorations of mediums and modes are united by an emphasis on process, with the use of multiples and repetition as ritualistic discovery. She has an appreciation for the inherent language of materials and the variations and flaws in handmade objects.

Teruko received her BFA from San Francisco Art Institute and her MFA from UT Austin. She has exhibited in the U.S., Mexico, and Canada. She was an OX-Bow School of Art Fellow, a mentee artist in the City of Austin’s Launchpad program for emerging public artists, featured in the 2017 TX Biennial, and one of five Austin artists invited to create work for New York City Highline’s traveling joint art initiative “New Monuments for New Cities.” Since moving from Texas to Washington to be closer to family, she was selected as a 2020 Public Art Reaching Community artist with the City of Tacoma and will be exhibiting at the Bellwether Festival in Bellevue in 2021. She lives and works in University Place with her husband, two young children, and three cats.

Abby E. Murray, Collateral Editor in Chief:

Hi, everyone. I’m Abby Murray and I’m the editor of Collateral. I am here today with Teruko Nimura and we are going to be talking about her work. This is for our spring issue that’ll be going live on May 15th. Teruko has a lot of different sculpture work to talk about, a lot of range. I’m just so glad that she’s here to talk with us about the impact of her work. And we’ll see in some of the discussion too, how her work touches on the theme of Collateral’s mission. Welcome.

Teruko Nimura, Artist, Tacoma WA:

Thank you. I’m so happy to be here.

Abby:

I’m really glad to have you. I’m really interested in—I really like hearing artists’ stories about how they chose different mediums, especially when they work in multiple mediums. I want to know a little bit more about how you first approached—why sculpture, why this art form?

“It was satisfying—that desire to appreciate the senses of my work.”

Teruko:

Well, I started out doing drawings mainly. I loved pencil and charcoal, and those are both really physical mediums. You smudge them, you erase them, and I ended up using it almost as though I was rendering in three dimensions, because it was a flat surface but I would create a format of these blobs of flat color. I moved naturally to clay from that, which is also a really tactile medium. I think I’ve always been drawn to things that include or activate the senses—just personally—but also just my enjoyment in life, like my experiences and things.

I think, from drawing and touching the paper and the graphite, [I] went to clay. And then from clay, I did a lot of rendering the body, doing traditional figures in clay. I enjoyed that, but it was so technical. There’s so much to learn with clay and I still love it, but going to grad school, I had so many disasters with clay. I actually went in with an emphasis on clay and then started jumping to things that I could get my ideas out easier, and that was fabric and that was paper. Still sculptural mediums, tactile mediums, but they had less technical obstacles.

That just led me to installation. I jumped, I feel like, in this natural progression for me, starting with just the love of the tactile. And then the installations, I feel like with fabric and paper, they were able to activate all senses. It was satisfying—that desire to appreciate the senses of my work.

Abby:

Yeah. When I think of graphite and charcoal and smudging, you were saying, that’s an art form that it quite literally rubs off on you. You carry marks. You’re marked by your art.

Teruko:

Mm-hmm.

Hibakujumoku (Survivor Tree), 2018

Pressed Ginkgo Leaves, Dried, stretched and singed hog intestines

5” x 36” x 36”

Hibakujumoku is a Japanese term for a tree that survived the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. This installation explores the inherent language of materials to communicate the precarious cycle of loss and redemption.

Abby:

You can almost see where the artist has been just by looking at her hands.

Teruko:

Yeah. I did a performance piece, one of the only public performance pieces that I did, that was using a sculptural thing that I made out of paper, but I used charcoal as well. It ended up being like I was drawing on these objects almost, with the smudging of the charcoal. It was interesting that you say that, because I was starting to bridge all of these things together, all the mediums just started mixing around and then just expanded into installation and performance work.

Abby:

Yeah. I’m glad that you mentioned, too, that your work is physical work. That it started in drawing, which is physical, and so is sculpture, because I think we often forget that art is physical, including the literary arts, writing out or typing.

Teruko:

Mm-hmm.

Abby:

It’s something that we have to use our bodies for. Our bodies are present in our work as well. I’m glad that you mentioned that because not very many people bring that up.

“It was always easier for me to create, to understand, perform in space, rather than try to make the illusion of it.”

Teruko:

It was always easier for me to create, to understand, perform in space, rather than try to make the illusion of it. I couldn’t in two dimensions. So say with drawing or something, you have to use color and your understanding of light, to create a form. But in sculpture, you create the form and that’s where you start. I could touch it and I could see it and move it around, and that’s how my brain could understand it. It was easier for me to know it and study it.

Abby:

Yeah. Did you become an artist at a very young age? Did you recognize yourself as an artist when you were young?

Teruko:

I was always doing these periodic exclamations of like, “I’m bored. I’m bored,” all the time, “I’m bored.” And my sister started packing me these little backpacks. She called them “I'm bored bags” and they had things to help me, because I was always just needing to do something.

I think I started drawing really early as a way to divert some of my anxious energy. It helped to calm me, it helped with my hands busy. I was able to focus in my mind and could calm down and be more clear. [My sister] recognized that pretty early I think. I would go into my room and just draw all over my body. I wanted to cover myself in color for some reason. There were lots of markers just everywhere and my parents didn’t discourage it. They were okay with it. It washed off. It was fine. I think with that non-shaming, they let me do that and they encouraged me to do that, I think that helped to cultivate that being an artist is just what I want to do, and it’s okay.

Abby:

Yeah. Well, to recognize it as art—and I think sometimes we can tend not to recognize art when it is in the bodies and hands of young people—to hear that [your family] embraced that and also saw the practical reality that colors wash off.

“I would go into my room and just draw all over my body. I wanted to cover myself in color for some reason.”

Hibakujumoku (Survivor Tree), 2018

Teruko:

Yeah.

Abby:

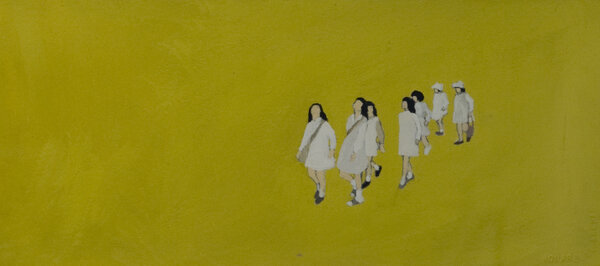

Yeah. Why not embrace it? Actually, that’s one of the things I wanted to say about your work, is that in looking at your different projects, all of them, really the common observation I have, is that they have such freedom of movement, not just in the three dimensional form, but also across the color spectrum. There’s always great contrast in your work, bright yellows and reds up against dark browns and blacks. I see that as movement. It appears that your sculptures are moving. As an artist, how do you perceive movement in sculpture?

Teruko:

I think I like to use repetition and color to create movement in static sculptural objects. I think for me, they express more when I’m asking the viewer to move with the work, like with their eye or with their body. With the way that I use repetition a lot or detail, I like to create an impression with an overall object and then hopefully the details or all the little things that are in the work, bring the viewer closer. And that movement of discovery or leaning in toward the work creates another layer of experience or understanding for the viewer. The details are important.

And then I’m hoping that once they see the details that brought them in, that they again move back and look again with the detail now understood or in mind. I try with the work, to have these layers of experience for the viewer to ask them to actively engage with the looking process in stages.

Abby:

Yeah.

Teruko:

I think with movement, that’s kind of not only visually, but sort of with the viewer in mind and their body and their experience of the work.

Abby:

Yeah. It’s funny that you say clay was so technical, when I look at the origami work that you’ve done and it seems very technical. I have yet to fold a paper crane without ruining it. To see such fine detail, the fine creases, the fine point, the bend versus the break. That’s something that I see in your work, so it’s funny when you say it’s so technical. I'm like, “What are you talking about?”

Teruko:

The definition of technical moves around.

Abby:

When you talk about the viewer of your work too, I wondered—and this wasn’t a question that I had sent to you beforehand—but I wonder, people always ask, “who is your audience?” I want to ask you, who is your audience? Who do you want to reach most with your work? Not necessarily who may be experiencing your art, but is there an audience that you want to reach that you may not have yet? Is there an ideal audience for your work?

Teruko:

An ideal audience… I feel like I always hope to shift perspective somehow. Maybe my ideal audience is somebody who maybe doesn’t see a lot of art or like thinking about art, but there’s some way that they access it, like a public piece that I’ve done or something they encounter outside that I’ve made. Ideally, it is somebody that I’ve sparked something in that maybe they didn’t realize. It doesn’t have to be the art world or anything, so any regular person.

Abby:

No, that makes sense I think, especially because your work touches on some universal human themes that apply to all of us. War impacts all of us, not just the people who are sculpting and are curating and visiting museums, it impacts all of us. I think that makes sense. I feel connected to you in that, as a poet, my ideal audience is someone who is suspicious of poetry, because I like to say I’m suspicious of it as well.

Teruko:

That’s wonderful. Yes.

“The details are important.”

Abby:

Yeah. Readers of Collateral will have a link to your work, but can you tell me a little bit about “For Every Sadako”? I want to know how this project was conceived and prepared and presented. It was the first of your work that I saw.

This is just a side story—I went to Catholic school when I was very, very young in Puyallup, Washington, and the nuns used to walk us from our school down to the site where Camp Harmony was, and Japanese and Japanese Americans [had been] behind fences there. My grandmother remembers playing with kids on the other side of the fence, kicking a ball, and running up and down. It’s now the fairgrounds, this place where you hear happy screams of people on rides and eating cotton candy. The nuns used to walk us down there and tell us what had taken place there and what was still there on the land. When I saw “For Every Sadako”, and having read the book, which is for children and young adults, it was very powerful to me. It brought me back to when I was small and when I was first starting to realize that grownups could be evil. That’s really disturbing as a kid.

Teruko:

Yeah.

Abby:

Your parents are constantly telling you, “You need to be kind. You need to be respectful because otherwise you’re going to fail at being and adult.” And then when we’re young, we inevitably learn that some adults missed the memo.

Anything you want to tell me about “For Every Sadako”?

Teruko:

Well, when I was six years old, I went to Japan with my parents and sister. We went to Hiroshima Peace Park, which has a giant monument to Sadako. I think of it now, looking back, that it was like the first public art piece that I encountered. It made a huge impact on me, because not only was it the first time I really understood that a child could die—and I was a child at the time—but that the reason that she died was not… it was external and it was something that was imposed upon her. And then of course the whole tragedy of Hiroshima. I also learned to fold cranes on that trip. It was a very tactile experience too, going to the site, experiencing the monument, learning the story, and then connecting with this other child that died, and realizing that I could die too. Then the following year, my father died unexpectedly.

That was this huge life event. I think through that loss and in turn, that kind of loss of a connection to my culture, or that side of my culture, because my mother is Filipino American. I’ve had this great desire to connect with Japanese culture and craft, in an attempt to connect again with my father in some ways.

I think that story, it just stayed with me and it continues to influence so much of my work. Now that we have so much tragedy in the world that I just can’t fathom and it overwhelms me on a daily basis, I think back to how I can process all of that. It’s just through making, I guess, trying to express or understand or communicate through making. [“For Every Sadako”] was inspired by the legend of the cranes and this wish for humanity really, to wake up and realize, with the coffin—it’s a mirrored coffin. If the viewer is looking at this object, then they’re implicated in this reality that you either have the potential to make this world better, in terms of anything I suppose, or you kind of stand by the wayside and become complicit.

That mirror is meant to bring the viewer in more, pull them in more beyond just a spectator. Their face if they look down, the cranes are above them. You can see that they become part of your work.

Abby:

Yeah.

Teruko:

And it’s almost dependent on them too.

Abby:

Yeah, definitely. It’s a dialogue piece, the reader needs to experience it.

Teruko:

Mm-hmm.

Abby:

Having known that you were six years old when you went to Japan, experiencing the coffin and the mirror in particular, has a new meaning.

Teruko:

Yeah.

Abby:

It’s a horrible new meaning, but it is also terribly vulnerable. You’re inspiring other artists in the making, to make through this devastation that we can’t even really articulate. It’s gotten so bad.

Teruko:

Yeah.

Abby:

What are your fears in creating? I mean I have my own as a poet, but I think all artists have, honestly, a string of fears. We could just list [them] over and over, and I’m afraid that, I’m afraid that…

Teruko:

Yeah.

Abby:

We’d have pages and pages, or worse, some kind of Mobius strip.

Teruko:

Yeah. It’s these cycles of things.

Abby:

Yeah.

Teruko:

Absolutely. Yes.

Abby:

What are your fears?

Teruko:

I think fear is definitely there almost every time I try to attempt to make anything. The fear that I won’t be able to make it, fear that I won’t be able to say what I want to say, fear that what I want to say is stupid or not worth saying, and fear that I’m not doing enough. It’s so much fear all of the time.

Abby:

Yeah.

Teruko:

Sadly, it does motivate. I know with the last couple of weeks, I did a really intense proposal for a public art project that I am hoping to get at Bainbridge Island. I was afraid the whole time, that I couldn’t. I was like, “I can’t, I’m just not ready. I can’t do it.” But I pushed through that fear and I surprised myself that what I could do; I actually was able to communicate what I wanted. I feel really happy with where the proposal went and I’m just hoping that it gets accepted. But I think that getting to the other side of that fear, that’s art-making for me in some ways too.

Abby:

You say you push through it. And I wonder (I feel artists are always trying to learn from one another, especially when it comes to enduring and processing our own fears) in that experience in particular, with this proposal, how did you push through it? Hindsight is a wonderful thing and now you can look back. You said that you surprised yourself, but how did you do it?

Teruko:

I wanted it so badly. I just feel like it’s such an amazing project. It’s part of the Japanese American Exclusion Memorial; there's a call for art to be put on the existing memorial or supplement the existing memorial. It was such a wonderful project that I just wanted it so badly. I don’t know. That’s all I can think of to say for that. It just seemed like the perfect opportunity and I just had to get through it.

Abby:

Yeah. Really embracing the want. I mean want is an action, it’s something that we do. It’s not something static. Wanting something is a way of pushing something, it makes sense to me. Before I get completely off track, “For Every Sadako” started when you, I would say, when you were six years old. How did you start it when you began working with materials for the installation?

Teruko:

I've been working with folding cranes for a while and just the potential of what just that gesture could communicate on its own. Knowing the legend and knowing this cultural connection and this story—sorry, my child is screaming. I don’t know if you can hear that…[Zoom life, people!]

Abby:

I can hear that and I’m so glad it’s not my kid.

Teruko:

Yeah. I’m starting to explore more materials, like the inherent language of materials and what materials can say on their own, but also then that gesture and how that can build meaning too.

Abby:

Mm-hmm.

Teruko:

I think that I was using the cranes a lot, just because of all of the wars and atrocities that are happening around the world. I had to use my lens somehow to talk about it.

Abby:

Mm-hmm.

Teruko:

That was the story that came to me, really to address all the injustices that are happening now around the world. …I'm not sure if I answered your question.

Abby:

You did. Thinking about, just at the tail end of your response, and you are acknowledging the impact of war on so many of us too, which we talked about in the beginning of the interview. We often talk about the impact of war on art and on artists. Collateral, specifically, is publishing work that examines the impact beyond the combat zone. So not the battle story, but the ramifications, the long lasting ripple effects of violent conflict. But I wondered, do you see it as reciprocal? And I’m asking this I guess, just artist to artist, because I’m curious, do you see art having an impact on violence in the world?

Teruko:

I have to hope that there is some sort of impact, that we are dampening it somehow, whether it’s been just at the smallest level where we sparked something in somebody and they decide that they want to be more involved in activism or somethings changes their perspective somehow. My greatest hope is that we just affect humanity, that we can show through our work what kind of damage that can have, like emotional, physical. And that it helps to reveal that humanity and stop the othering of the enemy somehow.

Abby:

Mm-hmm.

Teruko:

I have to hope that. I don’t know if there’s a real quantifiable impact, but I have to [hope].

Abby:

Yeah. I understand that. Just the repetition of, I have to hope that. Because I’m unfamiliar with what the alternative is.

Teruko:

Yeah.

Abby:

The alternative to hope isn’t something that I’m familiar with I guess. That makes sense. That’s something to think about. Speaking of repetition and how to keep going in spite of the horrible things that spark our work, do you have an artistic philosophy or mantra? Do you have something that always comes to mind that keeps pushing you forward?

Teruko:

I think that losing my father at such a young age, and then having that awareness so early of death and loss, thinking of every day as a gift is kind of the only thing that kind of, I feel like, keeps me going. You don’t ever know, but every day, what can you do and how can you make use of that day? Every day is a gift.

Abby:

Yeah, that makes sense. And it’s something that I haven’t…I think I needed to be reminded of that. Before I conclude the interview, I wanted to know, do you have any works in process right now that Collateral readers could check out? This interview will be featured on May 15th, but if you have stuff that’s coming out in 2021, I’d love to know about it.

Teruko:

Thank you. Yes. I was accepted as an artist for the public art reaching community program through the city of Tacoma. I was a cohort of I believe 10 or 12 artists. We did sort of a training session with the city. We were also enlisted to create a work, a temporary public project, in Tacoma. Some of them launched already. Some of them got delayed. Mine got delayed because of location and the pandemic and what have you. I’m going to be launching that sometime, either early summer, late spring, not quite sure, at one of the parks in Tacoma. The piece is about basically the pandemic and this fear of losing the ability to relate to one another, and this hope that we can come back together. I’m using the prayer flags basically. And if you can see behind me, there’s this black circle.

Abby:

Yeah.

Teruko:

That’s one of the sketches for the work, but it’s going to be this 12 x 12 foot series of flags. They’ll be all cut up in strands and then it’ll be a circle and it’ll be—it’s hard to explain. When you approach the work, it looks like the circle is not evident, you can’t see it. But when you walk around the work, the circle emerges. All the flags create the image of the circle. I’m trying to express a feeling of unity, that we move past the chaos and find the right perspective. And there it is, we’re connected again.

That’s the goal of the work and it should be up for a couple of weeks, probably out in one of the parks. If it happens before the issue comes out, I’ll let you know the specifics, but I’m still working through those with the city.

Abby:

Okay. Yeah. Again, with the movement of your work. The viewer has to move around it in order to see what emerges—that’s beautiful. And people can follow you on social media. Can you share how people can do that?

Teruko:

Yeah. My handle is my name, TerukoNimura_art. I share a lot of my process on that, and finished works and things.

Abby:

Awesome. Well, hopefully people will follow you on Instagram. I follow you on Instagram.

Teruko:

Thank you so much, Abby.

Abby:

Thank you so much Teruko; this has been really helpful. I want to go back and look at all of your art again now. Getting to know you a little bit and taking that into the experience of your work, I think makes it all the richer.

Teruko:

Oh, thank you so much. Thanks for taking the time.