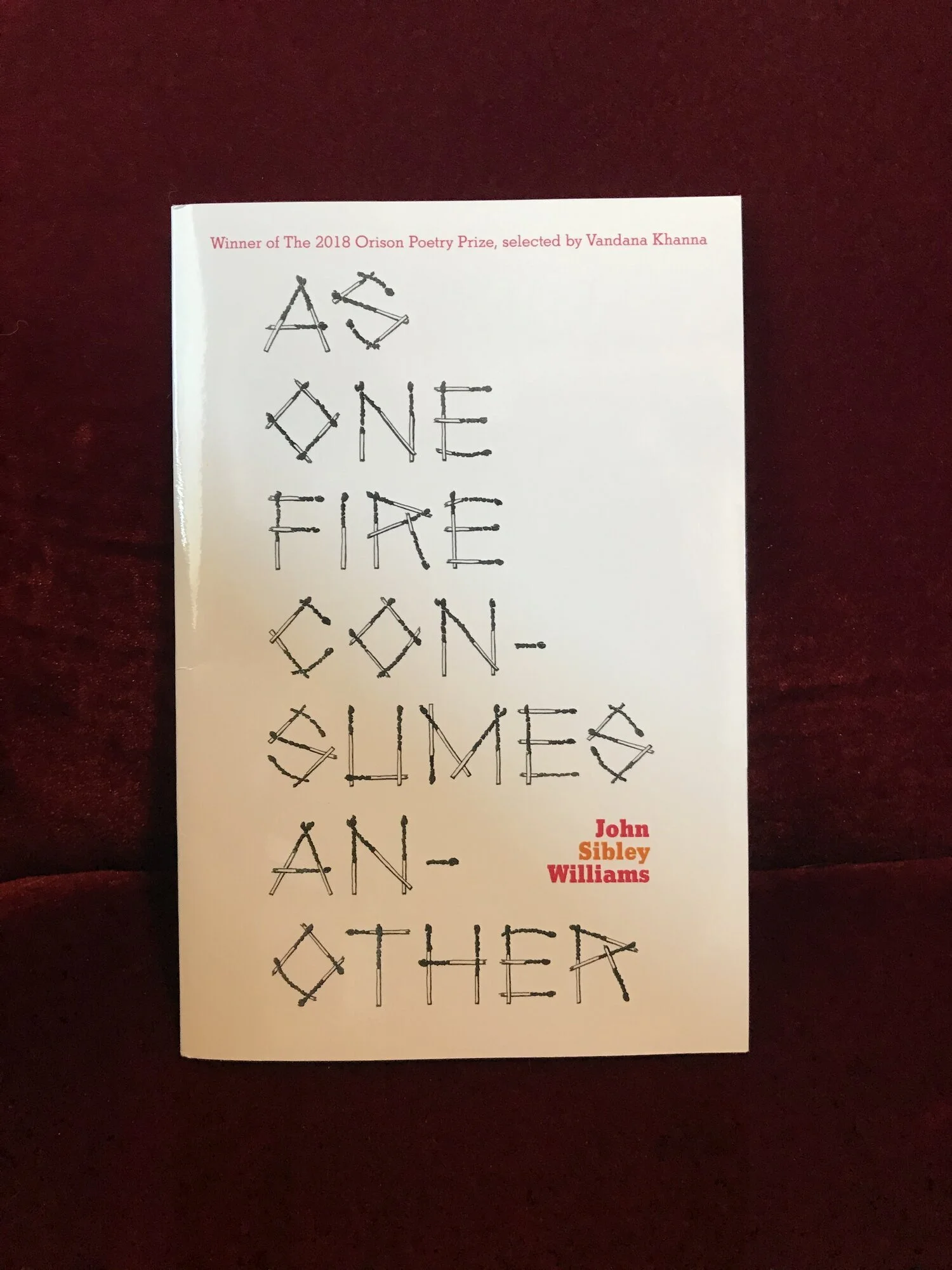

REVIEW OF JOHN SIBLEY WILLIAMS’ AS ONE FIRE CONSUMES ANOTHER

by Abby E. Murray

John Sibley Williams is on fire. Maybe you’ve heard his name echoing off the walls of recognition, receiving award after award this year—and it’s not even winter yet. He’s won the Ninth Letter Award for Poetry, Ruminate’s Janet B. McCabe Poetry Prize, and the JuxtaProse Chapbook Contest. He’s been a finalist for Arts & Letters’ Rumi Prize, the Crab Creek Review Poetry Prize, the Southern Humanities Review’s Auburn Witness Poetry Prize, and a slew of others.

Williams’ book As One Fire Consumes Another (not to be confused with Skin Memory, which launched this fall) caught the Orison Books Poetry Prize, judged by Vandana Khanna, and was also published this year. And that’s what I’m really here to write about—but damn. I met the poet in Tacoma and congratulated him on his accomplishments, and between the time I shook his hand and returned home after his reading, I’d gotten another newsletter email: John Sibley Williams won another prize. I’m not kidding.

So there are awards. But more importantly, the poems—the skill and voice, and the necessity of both.

As One Fire Consumes Another is an impressive technical and emotional feat, distinguishing itself as a collection of poems that employs identical narrow margins to restrain every poem, which are then justified to create a “cage” or column effect. (As a poet and editor, I thought, revising this must have been a nightmare. Funny enough, John confirmed this to be true! Every shift in letters had the power to throw off an entire poem’s line breaks and shape, and consequently its pacing. How does one wrestle with that? Slowly, I guess.)

The burning tide of violence that carries the book’s speaker from child to father in a time of war is just as noticeable, palpable on the page, intensified by the vast blank space.

When Williams visited Tacoma, where Collateral was launched, I caught his reading at King’s Books. When asked to read a poem most representative of the manuscript, he shared “The Crossing,” which closes out the book’s first section. The poem is delivered on a ribbon of instructions (“Tell me”… “Then tell me”… “Don’t tell me”… “Ask”… “Ask”… “Please tell me”) and swirled into the curves of that ribbon, we find the lament of a witness to war. In this poem, we are asked—or told—to question the tragic difference between humans and animals—our being “bound by maps, shifting allegiances.”

In “Here We Stand” (originally published in Collateral’s fall 2018 issue), it’s easy to see how Williams’ poetry compels the reader to revisit their understanding of war, patriotism, family, and peace:

…The father of our country is an

angry god, gutting youth from the

youthful, wood from the field for

bodies given back to the field. Rifle

clap. Contrails divide the sky. Many

smokes must meet to twine enough

rope for the dead to escape.

Ultimately, some of humanity’s most cherished values are at stake in this book, contained and turned over in our hands. The imagery of trust, land, belonging, parenthood, coping—it’s here, in a form more composed than we’re likely used to in our daily lives. The “cages” of these poems give shape to our complicated and chaotic struggles with gun violence, abuse, loss. It’s as if the poems hold our experiences still long enough for us to get a good look and remember why we carry them, and for that, I am grateful. This is poetry’s gift.

I have to add, too, that this poet is gifted with titles. “Us & Them.” “The Detainee Is Granted One Wish.” “Harm.” “The Invention of Childhood.” “There is No Such Thing as Trespass.” “At the Wrist.” “Salvage.” And finally, in a section all its own, “Reparations,” which makes a decision, claiming that this “has / always been for the dead.”

Give this collection a read—if not for the titles, for the skillful lines; if not for the complexity of life during war, for the first step in living it.